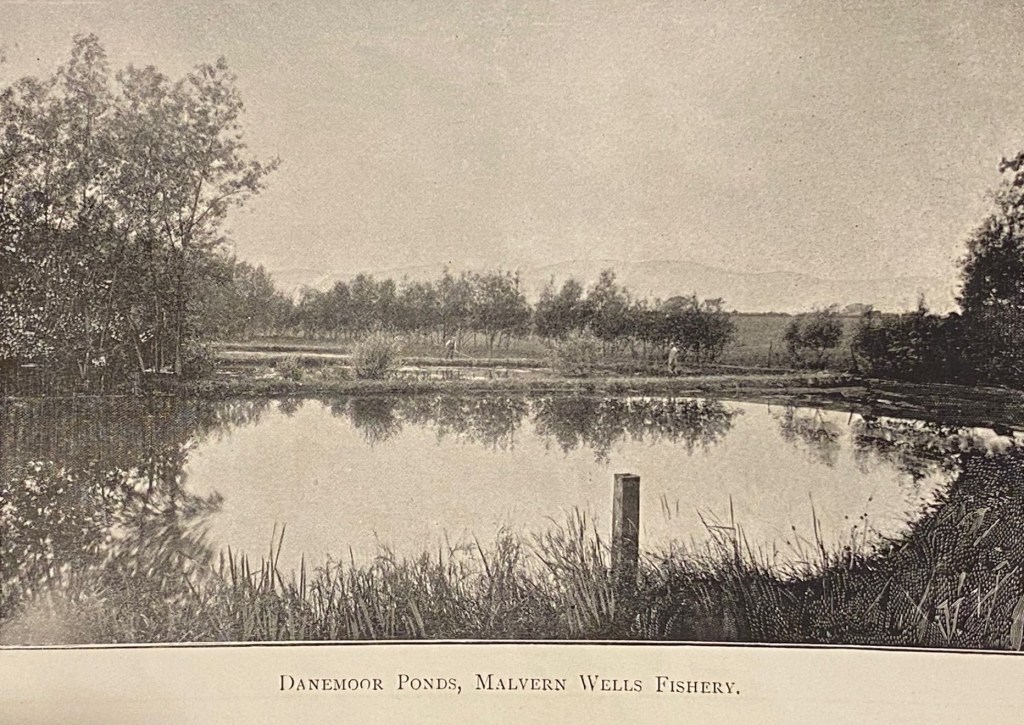

Danemoor Coppice is still marked on Ordnance Survey maps as a narrow strip of woodland between Danemoor Farm and Wood Farm (see map). A stream runs through it and there is a large pond at the eastern end. Patrick Campbell grew up in Welland in the 1930s and 40s and writes here about his memories of Danemoor Coppice, ‘Jones’s Wood’ as he knew it, when old fishery ponds still existed and the woodland was more extensive.

A series of fascinating images was recently posted online* by John Clements, whose family, close friends of my forebears, has farmed for generations at Brotheridge Green near Upton-on-Severn in South Worcestershire. The individual plates in an illustrated catalogue from William Burgess & Co, dated 1897, include photographs titled ‘View of Pheasantries at Malvern Wells’ and ‘Danemoor Ponds: Malvern Wells Fishery’, as well as earlier price lists of livestock, guns and line drawings of a wide variety of fiendish metal traps – including ones for poachers. All supplied by Wm. Burgess & Co, the proprietors of these twin establishments and self-proclaimed ‘Sportsmen’s Universal Providers’.

I say ‘fascinating’ because these pictures and price lists provide concrete evidence as to how the country landscape of this corner of England has changed over the past century and how, in a wider sense, we have become more humane and more considerate in our dealings with the natural world. Having said that, we have lost so many birds and beasts and so much of their habitat along the way, that there is nowadays no need for the hawk, kingfisher, heron, polecat and mole traps which Wm Burgess advertised with such enthusiasm. Of the eighty odd birds listed in his brochure as protected – and no raptor is included – a number are now threatened in the UK, including the quail, the bittern and the corncrake. Even familiars such as the barn owl and cuckoo are endangered.

I can offer no personal reminiscences about the pheasantry. Though it was sited on land adjacent to the fisheries – and the familiar outline of the Malvern Hills dominates the backdrop – it had, in my childhood, long since vanished: indeed, the sighting of a pheasant was always something of an event.

I had earlier encountered Danemoor Ponds on one of my many hikes around the countryside. It was, I recall, a hot July day, and I emerged from the tenebrous south end of Jones’s Wood to a most unexpected scene – five large, symmetrical expanses of water separated by narrow grassy dykes and fringed by alders, willows and reed mace. Beneath the surface of the last pool was something I had never seen before – long, subterranean shapes motionless in the warm upper layer of water. I threw a stick and they moved languidly. Pike. Big pike. Maybe ten or more pounds. The fiercest of British fishes. Confirmation soon came. There, high and dry in the willow herb, was a very dead pike that had maybe jumped out of its watery element to escape the jaws of hungrier brethren.

I later became close friends with Richard Lloyd whose father Tom owned Danemoor Farm, the site of these ponds. They marked the northern boundary of a two hundred acre estate, fed by a small rivulet that issued from a roach-stocked pool higher up on Henry Jones’s land at Wood Farm in Upper Welland. This brook snaked across open fields, entered the wood, and emerged again to flow into the first of the watery expanses.

That the five ponds were symmetrical was pretty obvious proof that they had been excavated manually, with a view to creating a commercial fishery. But the stratagem had not endured, at least not in the long term. What was a flourishing Victorian cottage industry that had won national awards as long ago as 1885, had now, sixty or so years on, reverted to nature’s embrace.

Nonetheless, the ponds still existed, now rented by the Severn River Board from the Lloyd family for the princely sum of £35 a year. The Board was probably responsible for dividing the original three into five and adding links between each stretch of water in the form of wooden sluices to control the flow. And as Richard points out in a helpful recent note, there were four valves to monitor the levels in each pond as well as a pipeline below the ponds which diverted water back to the stream.

It all sounds like an efficient arrangement. But the commercial heyday of the fisheries had obviously long since gone – the presence of rapacious pike was evidence of that. In a detailed description of the fishery in its prime, William Burgess’s brochure indicates that the original inhabitants had mainly been brown trout (salmo fario), not easy fish to breed. The ‘Fish Culture Establishment in Malvern Wells’ which appears to contain at least sixty tanks, was where it all started. Designed for ova and newly hatched fry, the young trout were then transferred from the hatchery to ‘a series of ponds’ (the Danemoor fisheries), up to ten feet deep, and designed specifically for ‘fry, another for yearlings and another for older fish’.

In an interesting aside, potential clients are informed that a railway station is conveniently close at hand, but counsels that ‘it is highly important that a suitable conveyance (on springs) should meet the train in which fish arrive, as delay at railway stations is often fatal owing to water not being kept in motion.’ Agitated water obviously meant oxygenated water. A precious cargo destined for the streams, lakes and tables of the hunting-shooting-fishing aristocracy of rural England.

The Burgess catalogue offered for sale – in addition to its staple of brown trout – perch and goldfish – presumably kept in separate conditions – ‘levenensis’ (sea snails with attractive shells from Madagascar), ‘fontinalis’ (willow moss, an aquatic plant for both cover and oxygen), and yearling ‘irideus’, rainbow trout not native to these isles, and presumably acquired from another source. The small print of patrons – perhaps one should say large print – is revealing: headed by Her Majesty the Queen and HRH the Prince of Wales, the impressive list of clients includes around 400 marquises, earls and other members of the English great and good.

Back to my childhood and the fish ponds. The word was out among my village pals that a mallard was nesting there, and since we were all avid egg-collectors, I decided on a sneaky search. It took all afternoon to find the nest, which was not, as I had expected, among the reeds, but in the crown of a pollarded willow. The pike had now gone, but I did note from a tell-tale ‘plop’ that a water vole had perhaps taken up residence. As for trout, no sign.

But there were brown trout in the vicinity. Less than a mile away was Marlbank Brook. It issues from springs in the granite outcrops of the Malvern Hills, cuts a deep swathe across Castlemorton Common and through Welland village, and eventually joins a larger confluence at Longdon. And it was home to trout. Not many and no great size, but beautiful stippled brown trout that I occasionally winkled out from the alder roots. I had often speculated as to how they had arrived there. And now perhaps I had an inkling. Though the brooks did not connect, someone who owned a stretch of stream had maybe popped a few in from the fishponds.

The confessional coda to this tale is both dispiriting and encouraging. Richard owned a 16 bore shotgun, and as teenagers we shot hares and wild duck from the cover of the grassy banks and sallies of the ponds. Next door, in Jones’s Wood we targeted woodpigeons, silhouetted against the night sky in the spectral winter trees. On the grassy pasture that was once home to pheasants, a covey of English partridges would whirr away in alarm, aware of our intentions. As far as I can recall, they survived.

Such activities and attitudes have long been in the past tense. When Richard left Danemoor Farm, having earlier inherited the estate from his father, the new owners decided to demolish the ancient broad-leaved woodland that was Jones’s Wood. No need for shotguns. Certainly no need for hawk or polecat traps.

* Malvern History Facebook page