From the late 17th century, Parliament increasingly took responsibility for repairing and maintaining roads through Turnpike Trusts. Acts authorised a Trust to levy tolls on road users and to use the income to repair and improve the road. They could also purchase property to widen or divert existing roads. The trusts were not-for-profit organisations and toll levels had a maximum set, so it was supposed to benefit everyone. The “turnpike” was actually the gate which blocked the road until the toll was paid, so when a road was referred to as being “turnpiked” it just meant that it had toll gates across it.

The first Turnpike Act of Parliament was in 1663 and it turnpiked part of the Great North Road. By 1772 local area trusts covered more than 11½ thousand miles of road. By the time the last Act was passed in 1836, there had been nearly a thousand Acts for new turnpike trusts in England and Wales, at which time turnpikes covered around 22 thousand miles of road – about a fifth of the entire road network.

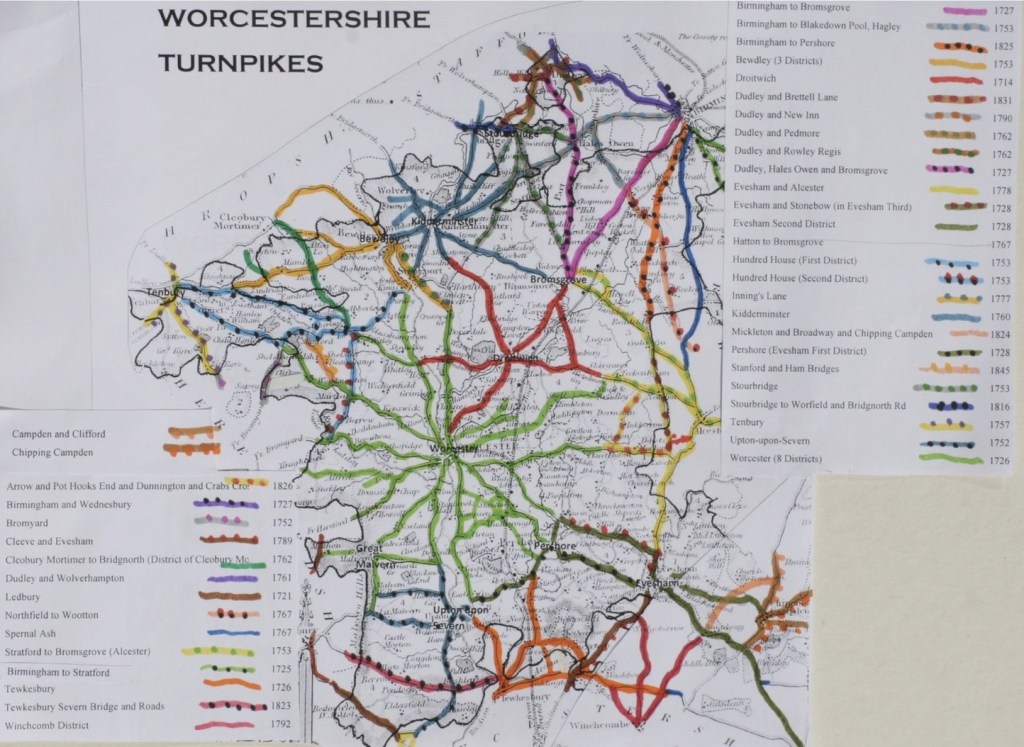

Locally, Welland was well served by turnpiked roads. The Upton-upon-Severn Trust included responsibility for Welland as part of the Worcester hub network, and the Ledbury Turnpike Trust (part of the Hereford hub network) linked into Worcester’s hub.

Welland had three tollhouses in close proximity, either in the parish or close to it. Little Malvern tollhouse on the A4104 was under the jurisdiction of the Upton Turnpike Trust, Twelve Mile Gate Cottage on the Malvern Wells road belonged to the Worcester Trust and the one just past The Malvern Hills Hotel beneath British Camp (see map) belonged to the Ledbury Turnpike Trust. Each tollhouse collected tolls for its own trust. Poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning made a reference to these three turnpikes in one of her diaries, writing that she had to pay at two tollgates when she went from home (near Wellington Heath) to visit her friend who lived at Malvern Wells, and if she also wanted to take the opportunity to drop down into Welland while in the vicinity, another toll charge would have to be paid.

Tollgates were often built at points were it was least likely that vehicles or horse users could evade payment, for example at bridges, crossroads or where the adjoining ground constricted the road. Hence many were built into a bank – as was the case with the three close to Welland. The tollhouses were generally placed outside urban areas. This avoided imposing tolls on local people and maximised the collection of charges on long-distance travellers. A downside was that these more isolated sites were vulnerable to thieves and highwaymen, so the windows of the tollhouse would routinely be fitted with stout bars and have built-in safes to protect the cash kept inside. However, many simple buildings were also built to house the pikemen who manned the gates on lesser highways. The classic design of a single story cottage with angled frontages dates from the 1820s when turnpike roads and the coach traffic they carried were at their peak.

Although the tollhouse itself was often the most prominent feature of the fare stage, as important to the toll collector was the gate. These were built to bar free passage along the road and were generally stout and substantial.

In 1840 there were still over five thousand tollhouses in England, but travellers had already started switching to the quicker railways, resulting in toll receipts dropping by a quarter over a period of just four years (from 1837 to 1841). In the 1870s, tollgates were opened to allow free passage – and just ten years later, the turnpike trusts ended and the tollhouses were gradually sold off.

Turnpike Trusts were responsible for the upkeep of roads and ensured they had a regular income by letting the tollgates to individuals. In some cases, tenants paid an annual rent to the trust and in return they were allowed to keep the tolls collected. Other times, the tollhouse was provided rent free but occupiers would hand over the tolls. It would appear from what we see on various census returns over the years that it was common for the wife to operate the toll gate and collect tolls during the day so the husband could work elsewhere.

The whole system of toll roads was very unpopular, as most people saw little improvement in the roads in the early days, found the frequent halts to pay the tolls very inconvenient and resented having to pay at all. In fact, it has been recorded that Mr Berington, a local Welland landowner, objected to paying the tolls – so the Trustees instructed the surveyor to pay him a visit and “acquaint him that the Trustees require him to pay the tolls at the gate the same as everyone else”.

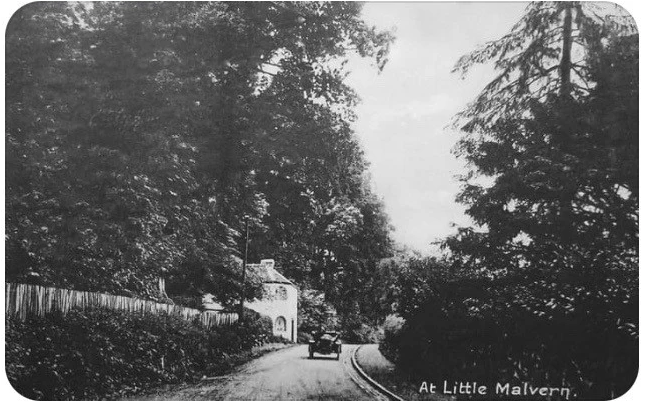

Little Malvern Tollhouse on the A4104 was built by the Upton-upon-Severn Turnpike Trust in 1822 at a cost of £56. It stood for over a hundred and fifty years at the top of the Welland to Upton Road just above Little Malvern Priory, after the sharp right hand bend but below the difficult junction with the A449 (see map). Windows faced both ways, so that there was a clear view in both directions of approaching traffic. This tollhouse was gifted to The Avoncroft Museum of Buildings in Bromsgrove in 1985 by the Berington Court Estate – it was subsequently removed and re-built, then restored and furnished. The tollhouse is a two storey brick building with a rear rubble wall of Malvern stone. The layout is somewhat quirky, being split level because it was built into a bank, so one enters the front at road level but exits the back door from the upper floor. During dismantling, a blocked up bread oven was discovered in the kitchen at the rear. The tollhouse had a timber built ‘earth closet’ (outside privy) that was also taken and erected next to the tollhouse at the museum.

The toll charge board currently on the front of the house is a not the original but a reconstruction, however, it is typical of the standard type of board that would have been displayed in the purpose built, arched niche in the front facade brickwork.

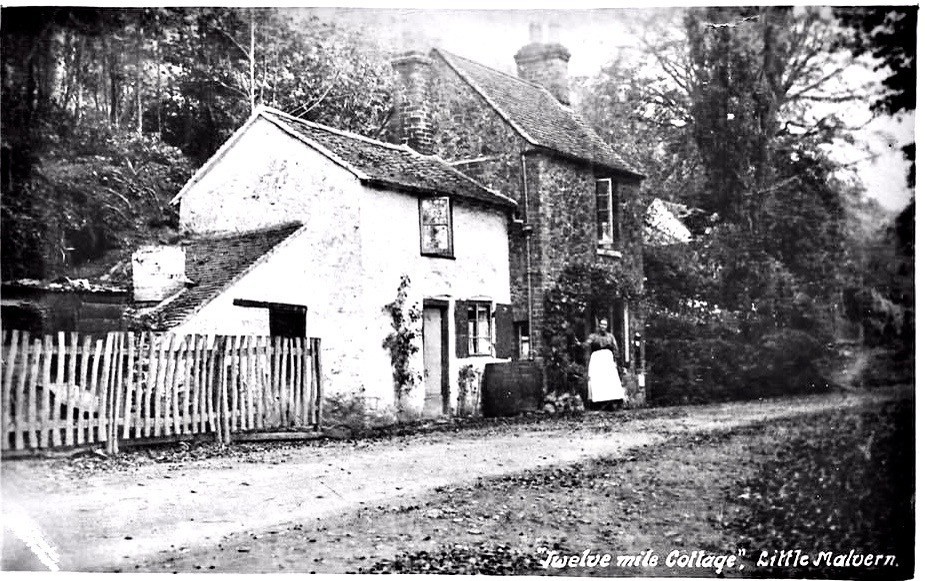

Twelve Mile Gate Cottage (see map for the location of the building, now demolished) was so called because it was exactly twelve miles from there to Worcester Cross, which is the crossroads right at the top of Broad Street, at its junction with High Street, St. Swithin’s Street and The Cross. Twelve Mile Gate Cottage had no electricity or running water, but it did have two gas mantles in the downstairs front room. The outside wall of the front room had a post box built into it. An outside privy was not uncommon then, but theirs was on the other side of the road, down some quite steep steps and several yards further on into the large garden area.

Milestones were erected by the Turnpike Trusts and can still be found along many roads. Only one in the parish of Welland still has its cast iron plate (see image below) although there is another just outside the parish, on the A4104 Welland Road by Lower Hook (see map). Both were erected by Upton’s Trust and have since been designated Listed Monuments by Historic England. Welland’s is on the Marlbank Road just west of the crossroads (see map). There are two other milestones along the A4104 in Welland but these no longer have plates (all three are marked MS on the map).