Streetend, a copyhold property

For a long time, the house on this site was the last one in Drake Street before Welland Common, hence the old name of ‘Streetend’. This name goes back at least to the manor of Welland rental of 1559 that refers to ‘the house at the Stretend’.

Streetend was a copyhold property belonging to the manor. Copyhold tenants owed specific duties towards the lord of the manor, the Bishop of Worcester, and were entitled to a copy of the title deed as recorded in the manorial court roll. Changes of tenancy were granted at the manorial courts. For example, at the court held in April 1633 it was reported that ‘Elinora Careles who held from the lord according to the custom of the aforesaid manor a cottage with curtilage called Streetend with two acres of land lying in Welland had died since the last court whereupon a heriot of 3s 4d fell due to the lord’. A heriot was a fee payable to the lord of the manor on the death of a tenant. The report goes on to say that Thomas Smith (possibly a relative) wanted to take over the tenancy and it was duly granted to him.

Fire & rebuilding

From later manorial correspondence it appears that the house partly burned down. A letter of 1807 from a Mr Bound reads, Yesterday I held court at Welland … I went over to look at Joseph Wagstaff’s cottage & premises he has rebuilt one end but it is a very indifferent place …’. Joseph Wagstaff took over the tenancy in 1789. The name Streetend seems to disappear about this time so perhaps it had fallen out of use by then.

We do not know whether the house that was burned was the one referred to in 1559 or a replacement.

By 1847, the tithe records show that the house and garden were owned by John Ward and occupied by Henry Wagstaff. The tithe map shows a small rectangular house in a comparatively large plot.

There should be references to the house in the 19th century census returns but unfortunately most of the Drake Street properties are not identified by name, making it difficult to match census entries with particular houses. Using the combination of census and land tax records, however, it is possible to identify some of the later occupants for Streetend.

George Jenkins

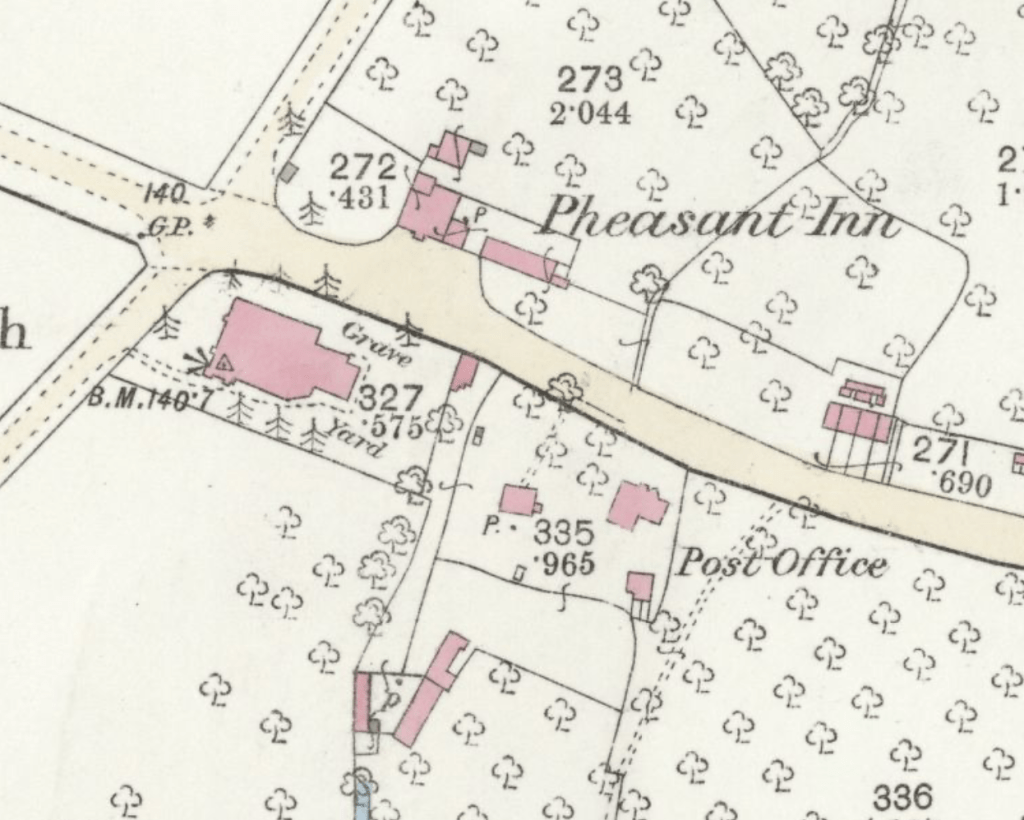

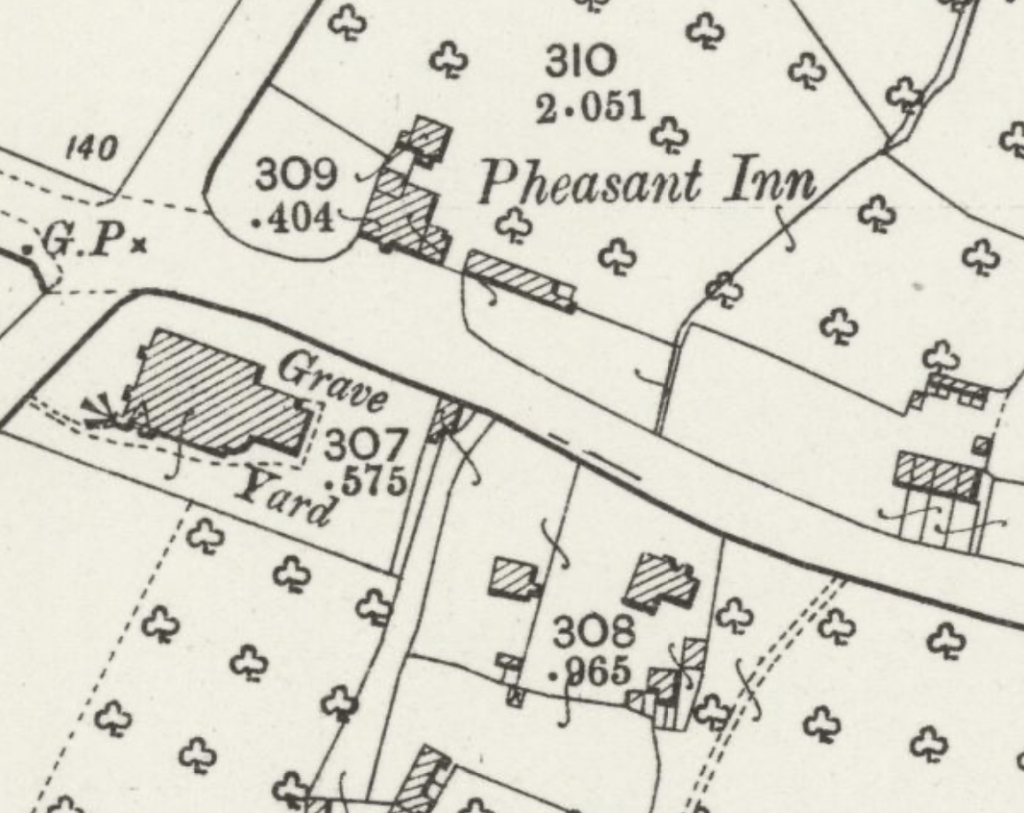

The OS map published in 1886 shows the plot had another building on it, the post office, as well as the cottage. George Jenkins, grocer and postmaster, owned both buildings and some of his tenants at the cottage can be identified.

| Ann Symonds/Simmonds | 1881, 1883 |

| William Bridges | 1885-1888 |

| Thomas King | 1889-1891 |

| Thomas & Elizabeth Bickley/Beckley | 1901 |

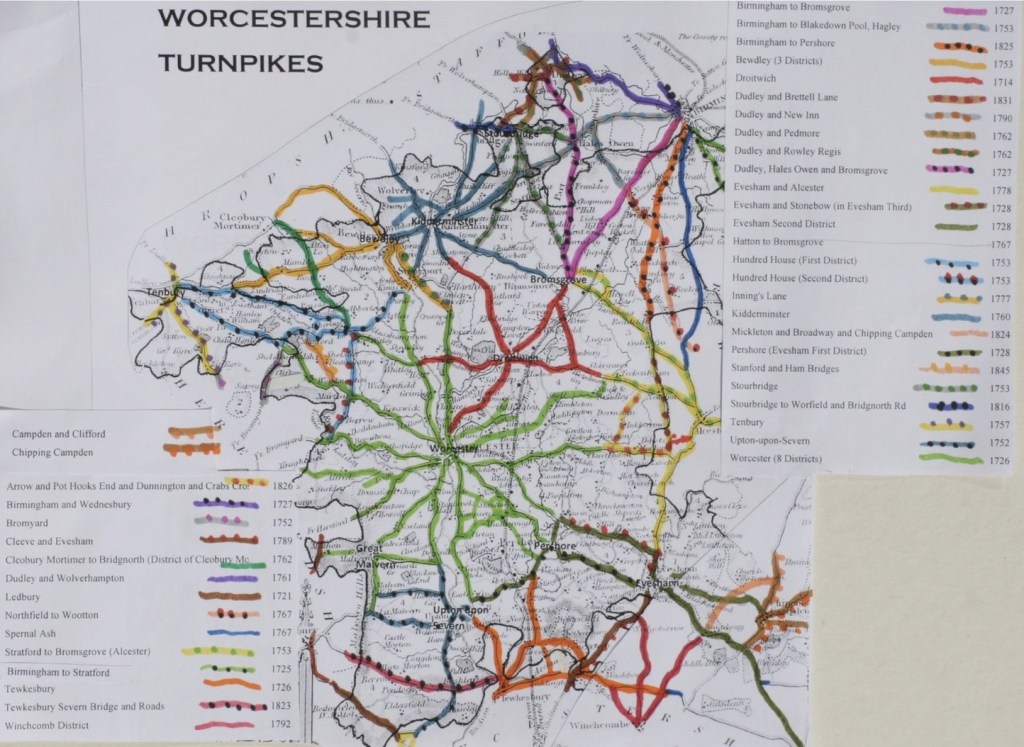

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

The 1904 map indicates the plot had been divided between the two properties. This may have been the first time in its long history that the Streetend two-acre plot had been reduced.

Mary Jenkins

The Valuation Office survey of 1910 describes the cottage as

‘Cottage & land 37 perches

Brick and Tile in Fair Repair

Kitchen, Back Kitchen & Washhouse

2 Bedrooms

Outside: Privy, Pigscot, Shed & Pump’

The owner was O B Cowley (probably Oswald Beach Cowley, an Upton solicitor) and the occupier M A Jenkins. This is Mary Ann Jenkins, widow of George Jenkins, and she was still there for the 1911 census.

William Stanley

Stevens Directory of 1928 names William Stanley as the occupier of Poplar Cottage and this is the earliest reference to the current house name found so far. In 1921 William Stanley was living in Drake Street but it is not clear whether he was at Poplar Cottage or still at Church Cottage, next door, where he was recorded in 1911. William was a labourer at Cutler’s Farm, his wife Sarah was charwoman for Rose Pudge at the Pheasant Hotel and the house had four rooms. The couple had two young sons, Frederick and Charles.

William and Sarah were still living in Poplar Cottage in September 1939, when the National Register was compiled. By this time, they were in their 70s, with William working as a gardener. Frederick, in his late 20s, was still living there. He delivered letters and telegrams and was also a ‘part-time poultry man’.

Poplar Cottage today

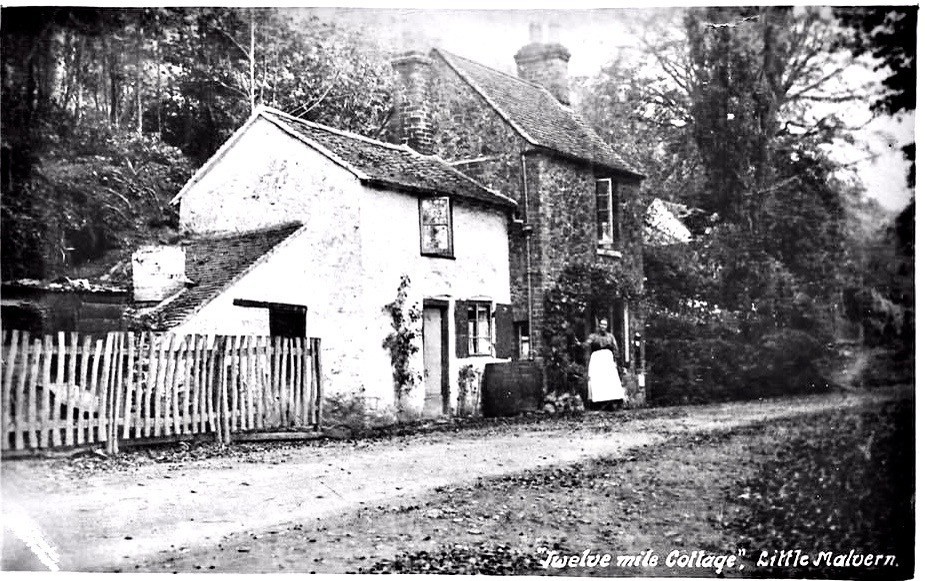

Looking at the house today, there is a sturdy chimney stack at one end and the roof ridge has a slightly wavy line, suggesting the presence of old timbers. A vertical line is just visible on the white paintwork between the downstairs windows and the porch. This might indicate the division between the remains of the original house (on the left) and the section built after the fire in the early 19th century.

The modern house is larger than it looks from the front, having been carefully extended at the rear and on the first floor.